Feature'Reds versus Whites' – when Anfield held public practice matches

It is now common practice for Liverpool FC to jet off to different destinations across the globe to take part in pre-season friendly matches during July and early August. Played in summer climates and often at iconic venues, it presents opportunities for overseas fans to see their heroes first-hand. More importantly, these matches seek to improve the fitness levels of the players, fine-tune tactics, as well as prepare the squad and management team for the rigorous demands of the season ahead.

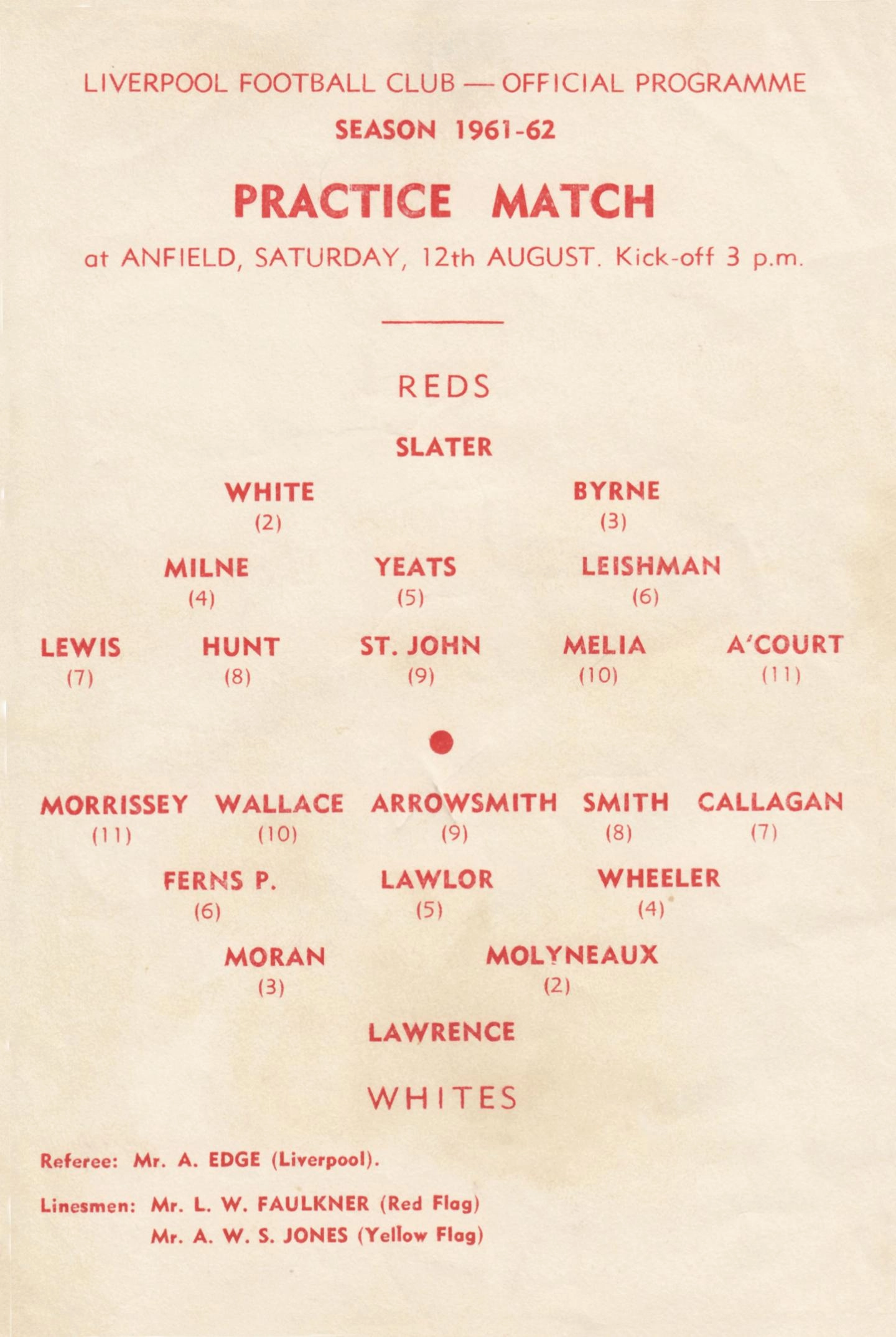

Travel like this began under Bill Shankly’s reign with the Reds flying to Germany for three friendly matches in preparation for their 1967-68 league campaign. All of this was a far cry from the old days when pre-season consisted of just one or more public practice matches in front of an Anfield crowd. These were club matches that pitted the first team against the reserves. The matches were commonly known as ‘Reds’ (Liverpool) versus ‘Whites’ (Liverpool Reserves) down to the colour of the jersey both teams wore.

What was pre-season like in those early years, in 1892 as the football club prepared for life in the Lancashire League, and the Anfield ground undergoing changes following Everton’s exodus to Goodison Park?

On August 10, 1892 the club held their first open practice session, witnessed by close to 6,000 spectators. It began with kicking drills before club skipper Andrew Hannah, who had previously captained Everton, split the players into two teams for an eight-a-side match. It gave those attending a chance to see for themselves some of the players that William Barclay and John McKenna had recruited.

After winning the Lancashire League in their first season, Liverpool along with Woolwich Arsenal were elected to the Football League. Again, part of season preparation work included a practice match. With the club more established, it was possible to assemble sufficient players to make this an 11-a-side game. This would continue each season, except 1895-96, when only 10 made it into each team “owing to the non-appearance of one or two local men”, the Liverpool Mercury newspaper reported the following day.

A notable absentee from the 1897 practice match was outside-left Harry Bradshaw, who earlier in the year had become the first Liverpool player to achieve international honours for England. His absence was somewhat of a surprise to the crowd until news filtered through that he had been excused on his wedding day.

By now, public practice matches were a formal part of the footballing calendar, though the Reserves did not always wear white. As early as 1914 they donned striped shirts to take part and this policy continued across the majority of seasons through to 1927. On these occasions, the fixture was billed as ‘Reds versus Stripes’.

The tradition of these matches was maintained, despite two World Wars. With the war effort in full swing, the club were forced to rely, from time to time, on players from other clubs to make up the numbers.

The start of the 1939-40 season brought some firsts: with the outbreak of World War II just around the corner, 24 Liverpool players undertook eight days’ Territorial training on the Gower Peninsula. They joined the 9th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment at Langrove army camp, near Swansea. Players performed army duties, as well as football practice under the watchful eye of manager George Kay, who was later joined by head trainer Albert Shelley. Staff back at Anfield hastily arranged to send the requisite football jerseys to Wales, and the following evening a Reds versus Whites practice match took place, much to the delight of all those at the army barracks. Players on view included club captain Matt Busby, Willie Fagan, and Cyril Done.

After the squad had returned to Liverpool, the players wore shirts with numbers on the back in the next practice match. This was the first time an Anfield crowd had seen such a thing. The Football League had made shirt numbers a statutory measure for the new season.

These fixtures, much like today’s pre-season friendlies, gave supporters an opportunity to cast their eyes over how the new signings were bedding into the team. Meanwhile, it offered the Liverpool committee a chance to tweak, where necessary, their plans for the season ahead. It also enabled less established players and trialists to force their way into one of the Liverpool teams.

Take, for example, the 1951 match in which the Whites’ goalkeeper, Cyril Sidlow, at half-time made way for Alan Sloan, a 15-year-old schoolboy, who pulled off many impressive saves. Based on his performance, Liverpool manager Don Welsh offered him an “immediate trial”.

In the same match, amateur Jack Farran, an 18-year-old outside-left from Manchester, was given an opportunity – a last-minute replacement for Norman Mitchell, of Newcastle, who was onboard a late-running train.

Some players were not so fortunate in these matches. Striker Jack Parkinson, after less than 15 minutes’ play in the final 1907 practice match, was injured in a collision with Reds goalkeeper Sam Hardy. Parkinson was forced to leave the field with concussion and minus two teeth. It unsettled the Whites, who crashed to a 5-0 defeat.

Dick Edmed, a right winger, made his comeback in the last of the 1931 matches, having missed all of the previous season with a cartilage injury, but it wasn’t long before he was carried off early in the first half with a damaged knee. The result didn’t go his way either, the Whites taking a stern beating 7-4.

In the last practice match of 1939, South African-born Arthur Riley dislocated his little finger on his right hand when parrying away a shot from Bill Jones. Left-back [Bernard] Ramsden stood in goal before handing over the gloves at the interval to another South African, Dirk Kemp. During the aftermath, there were calls in the local newspaper, the Evening Express, to abolish practice matches. Arguing that it emphasises the “grave danger of such games in which, maybe, one side plays at half pace and the other tries to pull out that little bit extra”.

Proceeds from every public practice match were donated to local charities. In the early seasons, a single charity received all the monies. This quickly expanded into many different groups, often reaching up to 20 or so charities in and around the Liverpool area.

The list of donations appeared on the home programme shortly after the season had started. Beneficiaries included Liverpool hospitals and nursing homes, National Institute for the Blind, St John’s Ambulance Society, Liverpool Police Orphanage, British Merchant Seamen, League of Welldoers and many more.

Shankly, in his third season as Liverpool manager, scrapped the Reds versus Whites fixture. After a six-year hiatus, pre-season matches were back in the calendar, but he chose to take his squad further afield for games against top-class continental opposition.

NewsLFC donates more than £590k to support apprenticeships and job creation in Liverpool City Region

VideoWomen's League Cup highlights: Newcastle 1-6 Liverpool

NewsWSL: Liverpool v Brighton fixture rescheduled

FeatureIn stats: How Mohamed Salah scored 100 LFC goals away from Anfield

StreamTuesday: Watch Liverpool's pre-Real Madrid press conference live