'England's No.1!' and 'an inspiration by being himself' - remembering Ray Clemence

Liverpool's dominance during the late 1970s and early 1980s was punctuated by freeze-frame incidents that perfectly captured a player's unique contribution to the cause.

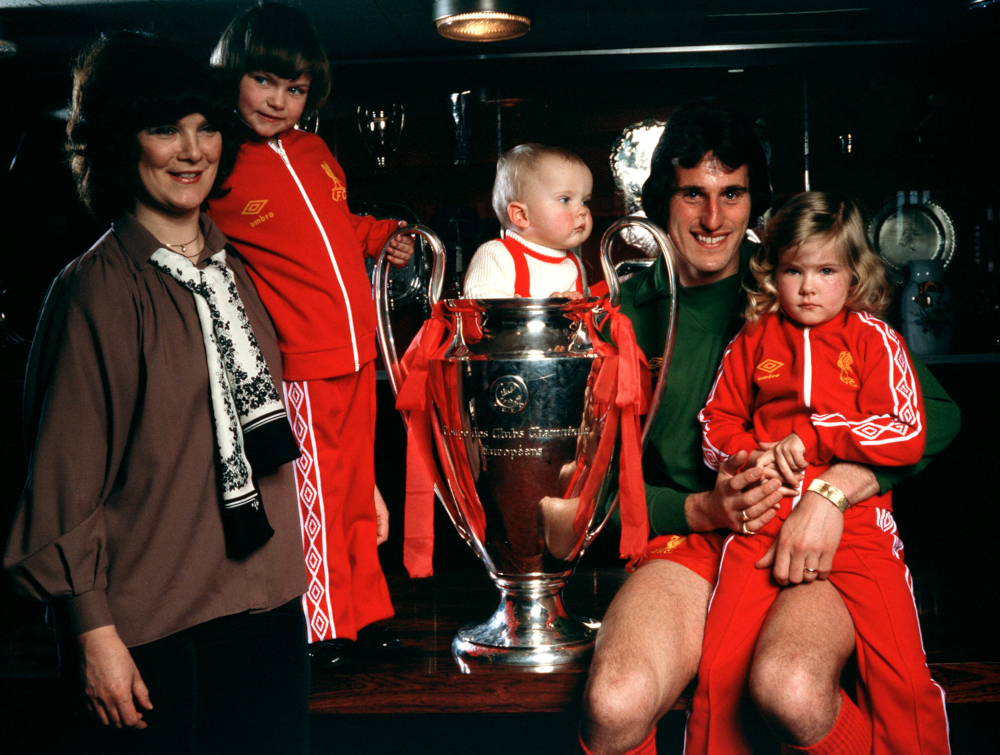

Almost all of Bob Paisley’s trusted lieutenants of that era enjoyed their own special moment. Tommy Smith had Rome ’77; Alan Kennedy had Paris ’81; Kenny Dalglish had, well, too many to mention. But one member of that squad managed to have a defining moment when playing for a different club altogether.

If you hadn’t already watched it before then, there’s a good chance you’ve seen the clip somewhere on social media since Sunday afternoon, when it was announced Ray Clemence had sadly passed away aged 72.

The date is May 15, 1982, and Liverpool, needing a win to be assured of their fifth First Division title in seven seasons, are 1-0 down at half-time at home to a formidable Tottenham Hotspur XI that had posed a genuine threat to the Reds’ domestic hegemony that term, taking Paisley’s men to extra-time in the League Cup final and trailing them by two points with three games in hand at one point in the spring. As the players emerge for the second half, Clemence, making his first return to Anfield as a Spurs player, trots over towards the huge undulating wave of faces that is the Kop; faces that had been left open-mouthed by his decision nine months earlier to draw a line under 14 years, 665 appearances and 13 major trophies on Merseyside.

The details are important, because what happens next is by no means inevitable. An almighty din of cheers and applause rises up from the steep terrace, eventually coalescing into one resounding chant: ‘England’s No.1! England’s, England’s No.1!’

Watch: A tribute to Ray Clemence

“Was it planned or spontaneous? A bit of both,” remembers Kopite Phil Aspinall. “The papers had said in the build-up to the game they were sure he’d get a good reception, but even in his wildest dreams I don’t think he’d have imagined such a boisterous ovation. It was thunderous. We were kicking into the Kop second half and needed to come from behind, and that’s when he came running down. As fans we were all disappointed with the way the game was going… but we couldn’t forget what a super player he had been for the Reds.”

Clemence – who teammate Phil Thompson recalls rarely acknowledging the Kop during his Liverpool days because he was so intensely focused on the job in hand – remains business-like, pulling on his gloves and going through his routine of stretches, but there’s no mistaking that the 33-year-old is visibly moved, returning the applause and punching the air as he arrives under the crossbar.

“For Ray to return to a standing ovation, on the day we were trying to win the league, when we’re 1-0 down, tells you everything that people thought about this very special man,” Thompson tells Liverpoolfc.com. “The ovation was just incredible. It showed how Liverpool fans, even in adversity at that particular time, loved their heroes, and he deserved every single clap he got off every single person.”

Clemence picked the ball out of his net three times in the second half, goals from Mark Lawrenson, Dalglish and Ronnie Whelan ensuring the deed was done in style. Thompson, who played all 90 minutes and received his sixth league winner’s medal at the age of just 28, was responsible for the second-most famous dash across the muddy Anfield turf that day, running the length of the pitch to embrace a man whose friendship and guidance had been invaluable almost a decade earlier, when he was an adolescent trying to navigate the tricky transition from midfielder to centre-half at Bill Shankly’s insistence.

“At the end of the game, when we had won it and were champions, the first thing that I did was not to hug or go to one of my teammates – I went straight up to Ray Clemence,” the former Liverpool captain and assistant manager continues. “I ran to the other end of the pitch to give him a hug, because he had played a major part for this football club. What Ray gave us is a big part of why we were such a great team, with a great bond as well. He was part of that.”

As a youngster toiling to make that final leap to first-team regular status, Clemence may well have recognised something of his past self in Thompson. Rags-to-riches yarns were more commonplace back then, but while he certainly wasn’t the only Liverpool player in that era to go from scrapping away in the lower leagues to gracing European Cup finals, Clemence’s origin story takes some beating.

From costing just £18,000 when he arrived from Scunthorpe United in 1967, and biding his time as the great Tommy Lawrence’s understudy for two-and-a-half years, to becoming England’s No.1. The same likely lad who hadn’t even tried his hand at goalkeeping until age 15, who was working for the council putting out deckchairs on Skegness beach aged 18, and who struggled so badly with goal-kicks in his early days at Anfield that Paisley is said to have removed the flags from the top of the stand as a psychological ploy, was by the early ‘70s capable of deciding European finals almost single-handedly, and the bane of many a top-rated attacker’s life.

Players like Jupp Heynckes, of Germany and Borussia Monchengladbach. When Aspinall attended the second leg of the 1973 UEFA Cup final he did so in full confidence of seeing Liverpool lift their first European trophy, following a 3-0 first-leg win at Anfield, but with 40 minutes played Gladbach were 2-0 up and clear favourites to finish the job on home turf. But they reckoned without the man in the baggy green jumper between the posts, who had made a vital penalty save from Heynckes in the first leg and kept the back door firmly shut for the remaining 50 minutes of the second.

“It looked bleak in the second leg, it really did, but Clemence was absolutely outstanding and you could see that it disheartened Gladbach,” Aspinall recalls. “He was the last line of defence whenever anyone got past Thompson or Hansen or whoever it happened to be, and when there were corners or high balls hanging in the air, he was up with his knees, taking no nonsense from big, bustling centre-forwards.”

Clemence was the scourge of Monchengladbach again in the 1977 European Cup final, making another decisive save from Uli Stielike when the score was 1-1 and the Germans were in the ascendancy. From Sepp Maier to Dino Zoff, the world was not short of outstanding goalkeepers in that era, but Clemence had few equals according to commentator Clive Tyldesley.

“It’s an overused word in football, but there were probably five or six ‘great’ players in that Liverpool team,” begins Tyldesley, who had a perfect view for many of the Reds’ triumphs under Paisley after joining Radio City in the spring of ’77. “You think how many great goalkeepers there were in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, but he was one of the finest two or three in the world at the time. So he was a truly great footballer, just as much as Kenny and Graeme [Souness] and Rushy [Ian Rush] and Jocky [Alan Hansen] were.

“And in a weird way that makes it even more difficult to be as great a person as he was, because you’re constantly receiving so much praise and attention. I think Liverpool fans have always liked triers, that’s just part of the northern psyche.

“Liverpool likes fighters, triers and people who wear their heart on their sleeve, and Ray was really quite an aggressive goalkeeper, courageous. Alisson Becker makes goalkeeping look a bit easier than Ray did, I think! But I wouldn’t compare them. Some greats have the ability to create space and time for themselves, and others are always on the limits. Ray was always on the limits, the saves he made were so physically brave, and that fearlessness probably won a lot of Merseyside hearts. He seemed like one of their own.”

While Tyldesley’s work allowed him to form close ties with many a member of Paisley’s squad, it was Clemence he grew closest to after the pair worked together on a Radio City talk show, his estimation of the player gradually coming to be dwarfed by his estimation of the man as the years passed and the former England goalkeeping coach dedicated time and energy to campaigning for cancer charities while batting with the disease himself.

“He lived the last 10 years or so as if each day were the last, and while he has taken every opportunity to travel and spend time with his family, particularly his grandchildren, he also made sure to experience as many things as possible, visit as many places, taste as many fine wines, eat as much food! He really did go for it. I can talk about the great football teams I’ve seen – Ray and his wife, Vee, is one of the greatest teams I’ve seen in my life. She’s the same woman he fell in love with all those years ago when he first came to Liverpool, and they were such a strong team.

“He was an inspiration, but without trying to be one. He wasn’t like some motivational speaker – he was an inspiration just by being Clem. He was an antidote to so much of the judgemental, cynical attitudes that seem to prevail in so many areas of life nowadays. It wasn’t that he had a naive optimism, quite the opposite, it was just fuelled by the fact he knew he had been fortunate in life, to have the opportunity to let his talents be seen and appreciated.”

Back in early October, Tyldesley sent out a Tweet informing his followers Clemence was unwell and encouraging them to send messages of support. The post received in excess of 1,000 replies, but when Clive spoke to Ray on Saturday, not realising it would be their last conversation, Ray told him that he had read every single one of them.

“I spoke to him at length on Saturday, so when I heard the news on Sunday it was the last thing I expected. The same rascal sense of humour was there when I spoke to him on Saturday, those were difficult conversations in the closing days, but he was so selfless,” said Tyldesley.

“Ray never allowed any of it to weigh him down, and that’s why I can confidently say that however great a goalkeeper he was, he was an even greater human being. It has been an absolute privilege to know him as well as I have done, and he is my hero. There’s so much in 21st-century life that weighs us down and pulls us back, and Ray wouldn’t let anything do that. He just kept marching forward, and anybody that was lucky enough to know him went with him.”