Remembering Ronnie Moran: 'He just wanted to do all right'

It's one of the scariest scenarios you can face as a child.

You’ve booted a ball through the front-room window and now there’s an agonising wait to see how your parents react.

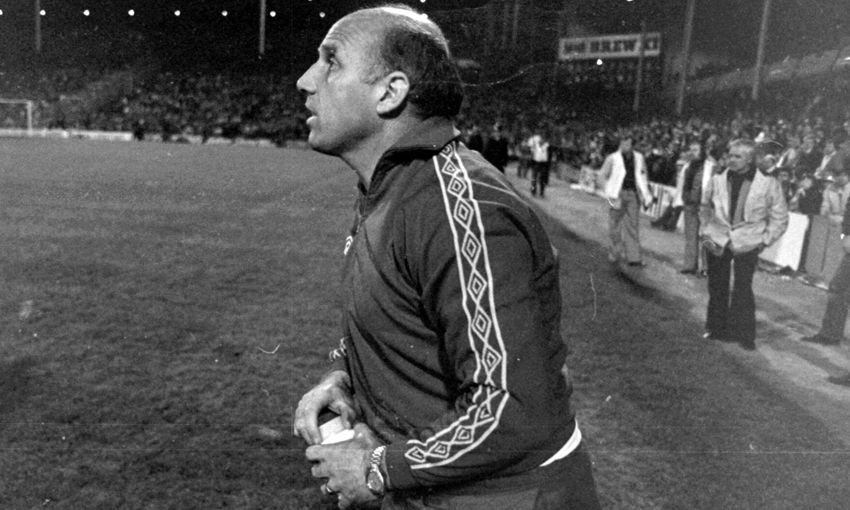

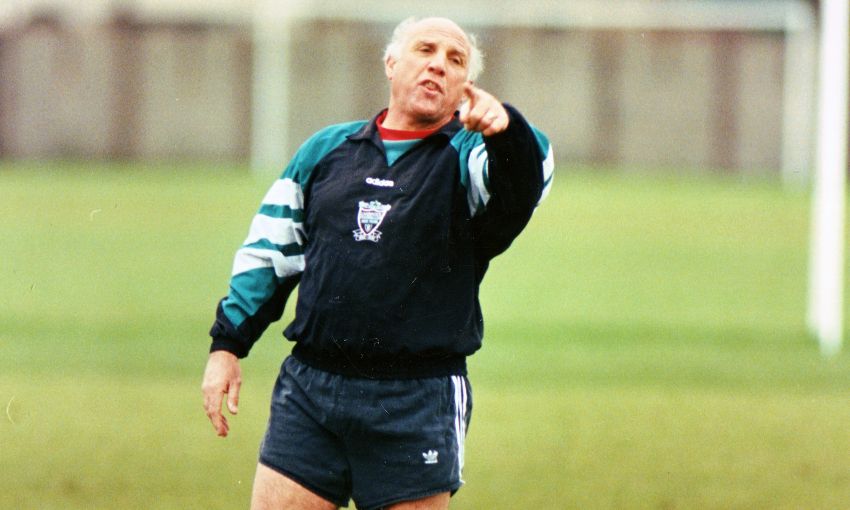

Now imagine it’s the seventies, it’s your dad’s birthday, and your dad is Ronnie Moran – otherwise known as ‘Sergeant Major’, or ‘Bad Cop’. A man feared by every member of the Liverpool squad at a time when it contained some of British football’s most formidable old-school hardmen.

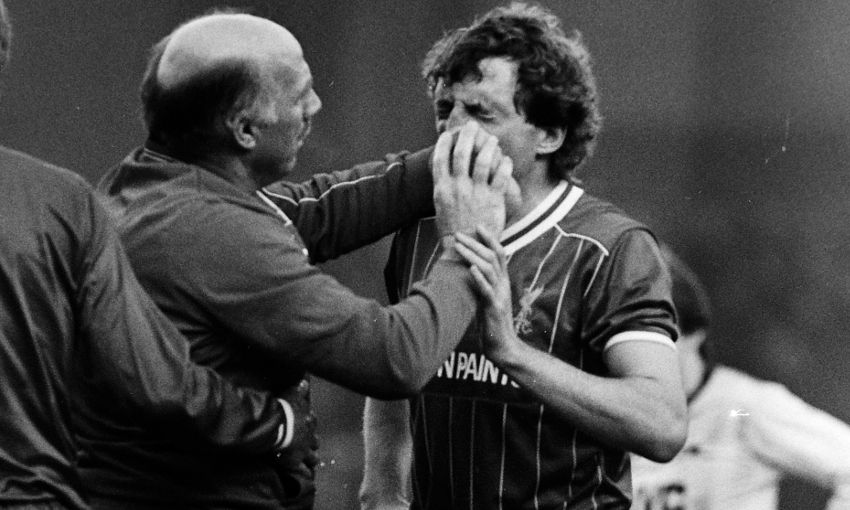

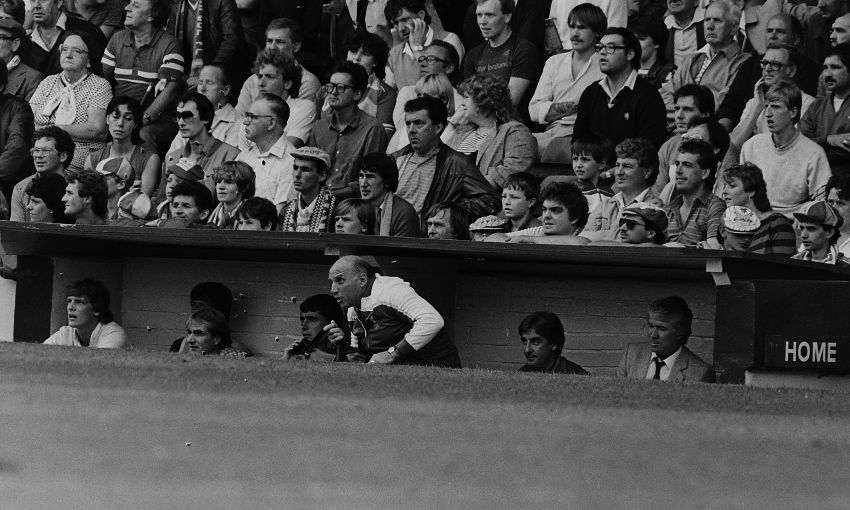

“We’d won 5-0 on a Saturday, you’d come in on the Monday morning and Ronnie Moran would be shouting: ‘Who’d you think you are? We’ve got a game next week!’” former Reds captain Phil Thompson recalled in an LFCTV documentary broadcast back in 2014. “You got nothing for what you’d just done on a Saturday, he’d be hammering you, and we as players would be going: ‘What’s up with this guy? We’ve just won 5-0.’”

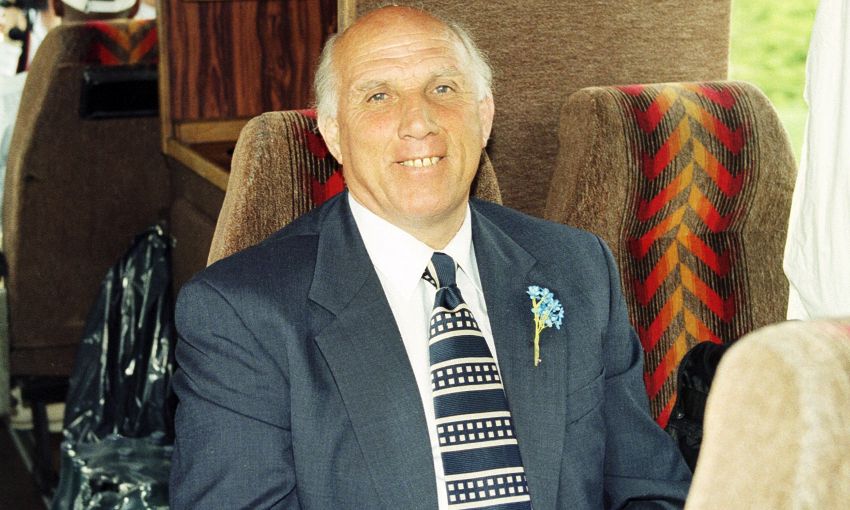

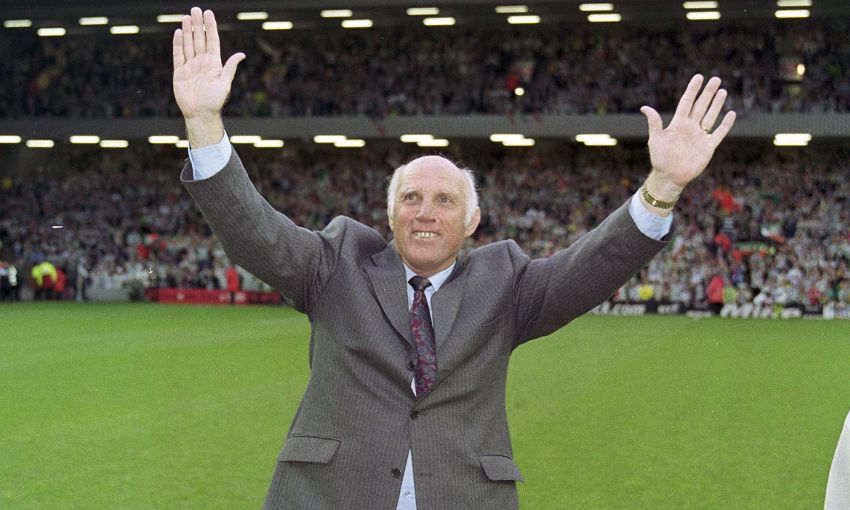

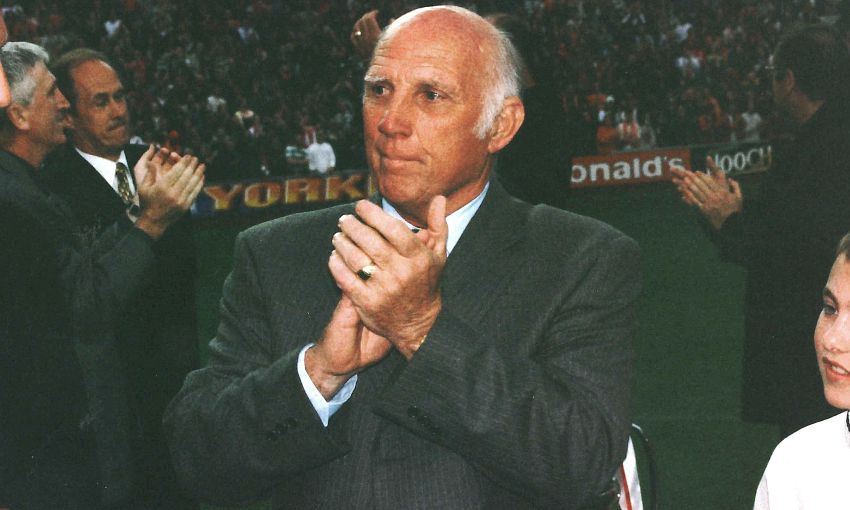

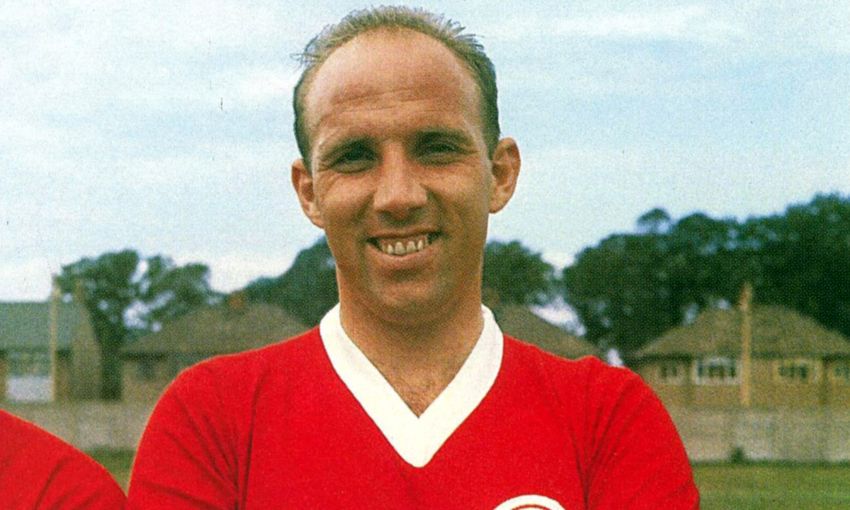

On what would have been Moran’s 85th birthday, today provides an appropriate time to reflect on the legacy of ‘Bugsy’. Not that there’s any chance of him being forgotten any time soon, such is his legacy at Liverpool Football Club. Indeed, since 2014 a flag bearing his image has regularly appeared on the Kop – probably the ultimate expression of affection where Liverpool fans are concerned.

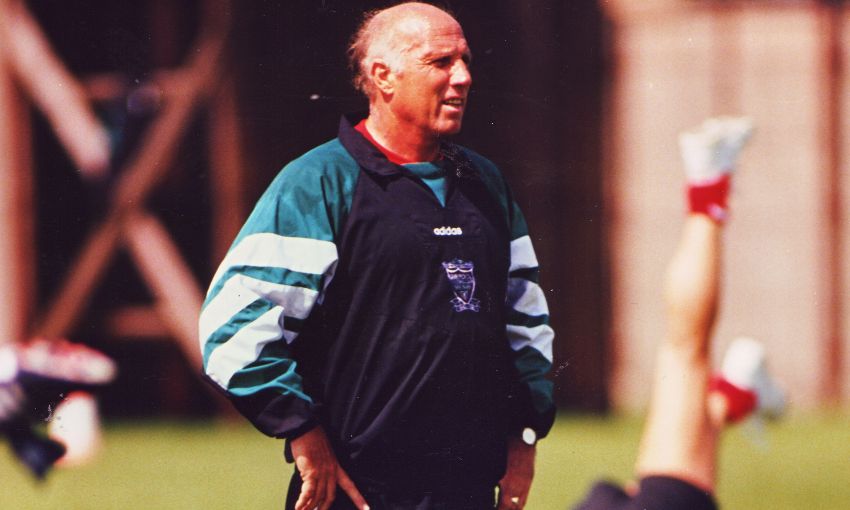

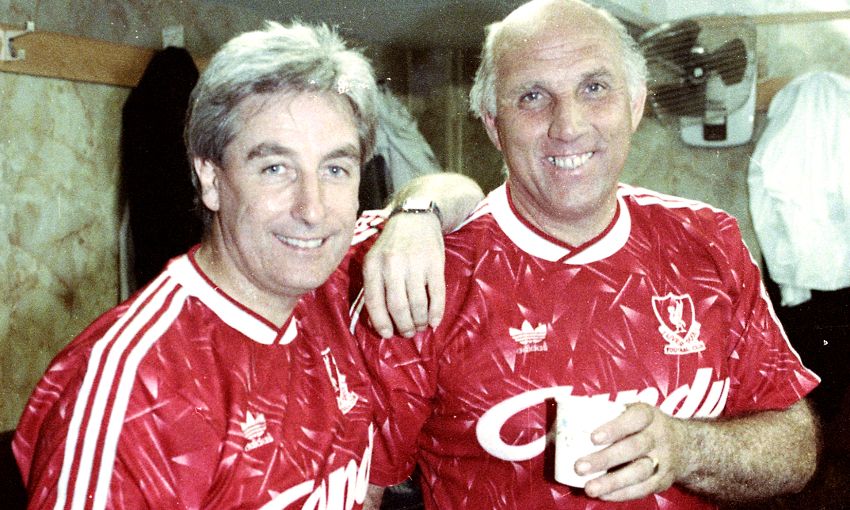

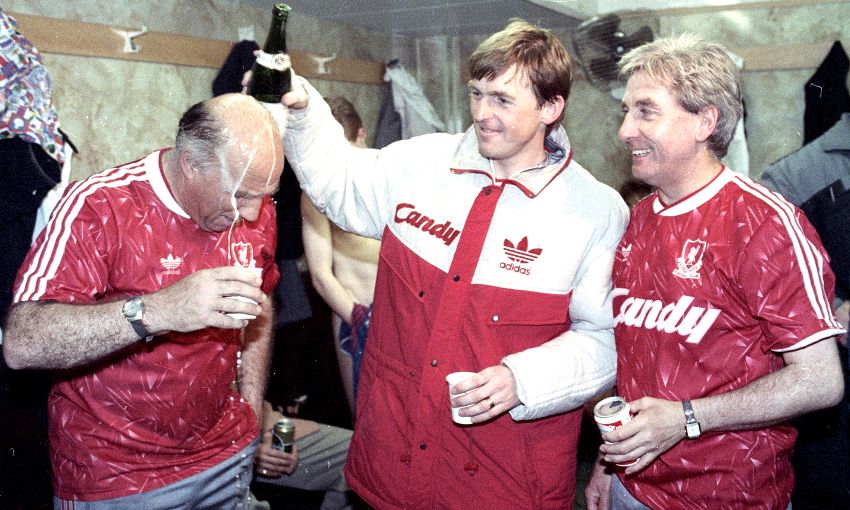

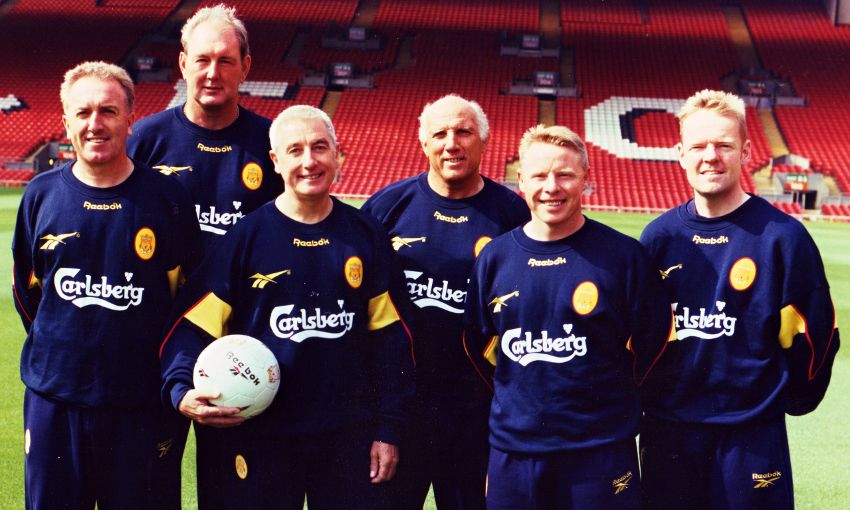

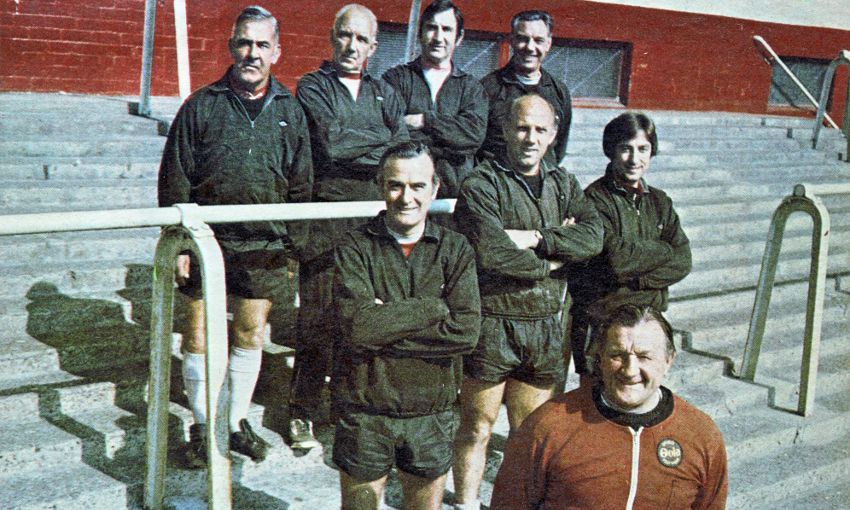

That admiration does not stem merely from the amount of time he spent at the club – a total of 49 years as player, reserve-team coach, physio, first-team coach, assistant manager, caretaker manager and founding member of the famous Boot Room.

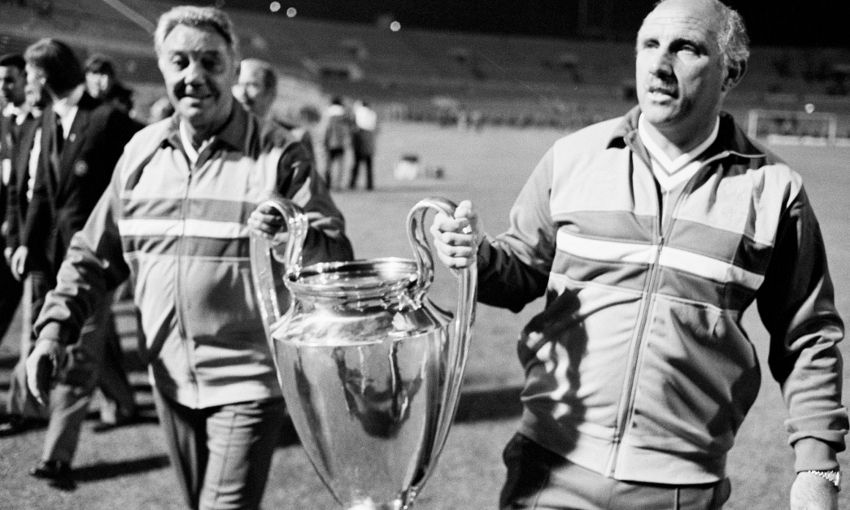

A keeper of traditions and an enforcer of standards, having been a major part of trophy wins achieved under Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley, Joe Fagan and Kenny Dalglish, he arguably understood the principles that underpinned Liverpool’s success better than anyone else.

Bugsy Moran: A tribute to Liverpool's sergeant major

But let’s return to that smashed window in Thornton before going any further.

“It didn’t just hit the window, you know!” the culprit, Ronnie’s son Paul, insists with a laugh. “We had a set of metal goals in the back garden, and it hit the bar, bounced up, hit the fence and then hit the window.”

If the incident had taken place at Melwood, Bugsy’s reaction may well have been volcanic, but he was a very different character at home.

“It always used to get mentioned on his birthday, that his present from me had been putting the ball through the window. But he didn’t mind, he would try to explain to people how it had happened,” explains Paul.

“I always say, he didn’t exactly tell us to come down for our tea in the style of telling Alan Kennedy to get into position, when thousands of people could still hear him above all the crowd noise. You’d get into trouble if you did things wrong, but it wasn’t like a constant stream of shouting instructions in the house.”

Paul’s childhood and adolescence had a surreal tinge, growing up a Liverpool fan at a time when the Reds were arguably the best team on the planet, and one of the men at the heart of it all just so happens to be your father. Still of primary school age, he had the run of Anfield when Ronnie took charge of reserve-team fixtures there in the early 1970s – the Scouse equivalent of being handed the keys to your favourite theme park.

“I was 12 when Dad joined up with the first team, but from the age of seven I would go to reserve games with him,” he remembers. “When you went to reserve games at Anfield the players would basically be in front of you when you went in and there was another bit of the dressing room where the people who weren’t playing used to sit. You would just sit there, out the way, and listen. I used to be made up with stuff like that. Sometimes I’d go on the Kop and be an unofficial ball boy. You could wander around, but you’d miss out on what was being said in the dugout, and that used to be funny.”

In later years, with the silverware continuing to stream into the Anfield trophy room at a rate of knots, Paul became a committed member of the travelling Kop, but his status as the son of an icon didn’t spare him from the ridicule of one particular recurring joke.

“Once it got to season 1979-80 and I was about 17, 18, we started going home and away every week,” he recalls. “I went to every league game during the 1983-84 treble season; there were 67 games in total that year and I went to 64. But I wouldn’t go with my dad, people used to say: ‘It’s easy for you’. And I’d go: ‘It isn’t!’

“One of the lads I went with used to shout my dad if he went onto the pitch to treat someone. As my dad was walking round in front of the Liverpool fans he would shout, ‘Dad!’, and my dad would look to where I was. I used to say to my dad: ‘Don’t look if anyone shouts ‘Dad’, because it’s not me! I’m your only son and it’s not me!’ Everyone would be laughing, because it was all the same people at every game, and in the end there would be quite a few people shouting ‘Dad!’ It was like a joke thing in the end, I think he used to look deliberately because he knew it got me in trouble with everyone I was sitting with!”

A keen photographer, Paul is a regular at youth and non-league games across the north west nowadays, either taking photos or supporting his son, who plays as a goalkeeper. The 57-year-old had the opportunity to create a lasting tribute to his father when he collaborated with Arnie Baldursson and Carl Clemente, both of LFCHistory.net, on the biography Mr Liverpool, published two years ago today on Ronnie’s birthday.

“Other than my family, the book is the best thing I’ve done in my life,” Paul states. “I was so happy we got it out there before my dad died, which wasn’t deliberate. We did it in about a year without seeing each other once; I’m in Liverpool, Carl’s in Murcia and Arnie’s in Reykjavik. They would send me questions via email and Facebook Messenger, I would take two or three days to send them back a big long reply, then Carl would send it to Arnie and Arnie would make the chapters up.

“It was published on my dad’s 83rd birthday, February 28, then he was taken ill in the care home and taken to hospital on March 11. The doctors said he’d last 24 to 48 hours from the Monday, but because of the strength he had in him he lasted for 11 days. The doctors couldn’t believe it. It was a difficult time, but it’s another memory of him and how much he was loved by the family.”

50 Men Who Made LFC: Ronnie Moran

To overstate Moran’s rabble-rousing qualities would be as reductive as to linger on Paisley’s shyness or Fagan’s homespun wisdom. The red notepads he collated full of training drills and physical information – known as ‘Anfield bibles’ – speak to a fastidious mind, and just like the others he had the uncanny knack of delivering a straightforward piece of advice that cut right to the heart of an issue and stuck with players for years afterwards.

When he cautioned Graeme Souness against passing backwards, for example, during the Scot’s home debut in 1978.

“Get the ball in midfield and work, son,” he’s reported as saying in the Paisley biography Quiet Genius. “We don’t do that here.”

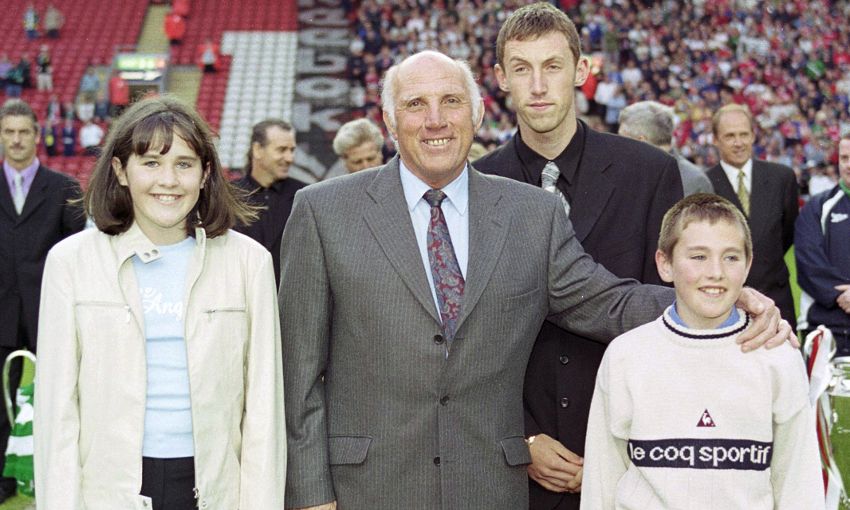

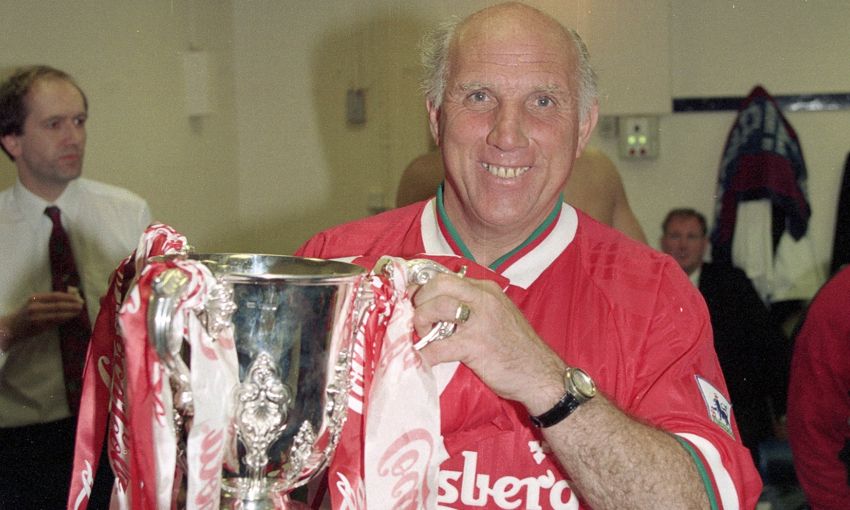

Fourteen years later, as Souness – who by then had taken on the role of Liverpool manager – was convalescing from heart surgery, Moran was tasked with leading the team out for the FA Cup final against Sunderland at Wembley, finally stepping out into the spotlight after all his years in the background.

His proudest moment? Not particularly, Paul concludes.

“He took every game as it comes, and just generally he was proud of the club’s achievements. What he used to say to us as a family was be brave, don’t wait for other people to do things all the time, make decisions for yourself. I always remember, when someone says, ‘What did your dad think about so-and-so?’, what he used to say is, ‘He was all right, him.’ And that was it. If people were able to say to my dad, ‘You did all right at the club’, that’s what he wanted. That was enough.”